This post on the Carthusian liqueur(s) is offered for the sake of completeness and as a sequel to the post on the Carthusian Monks, since they are the ones who make the excellent liqueur(s).

************

CHARTREUSE: The Queen of Liqueurs

*

Monks collecting the herbs needed to make Chartreuse

*

Herb room

*

Ah, Chartreuse!

Chartreuse is the “mysterious elixir that prolongs life” with its unique green color

and is shrouded in secrecy and mystique. This liqueur is made by legendary

Carthusian monks, contemplatives of the strictest Order in the Catholic Church.

Connoisseurs all over the world are familiar with its very distinctive and

mythical taste. This liqueur (one and only in its category) is

considered by many “a wonder of nature,”

“an unequaled masterpiece,” “peerless,” “a noble liqueur, rich, and satisfying,” a liqueur of which “one knows not how to write all its virtues.”

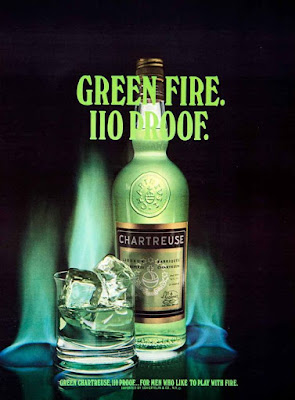

For many, it is also the liqueur “for

men who like to play with fire!” Yet, those sophisticated people who have

had the opportunity to taste it agree that Chartreuse is much more than that.

*

*

*

*

With the revival of the cocktail culture and craft

bartending, this iconic liqueur has once again become a favorite. If you

haven’t tried it, you must! If you hear someone ordering one “neat,” it is a

good bet that the person works in a restaurant/bar. Within the past decade, this Carthusian liqueur has

come out of the woodwork and has become the go-to drink for bartenders.

“Chartreuse fever” started slowly, but has come on strong, and bartenders have

gone from pouring one bottle of Chartreuse a month to four or five a week.

*

*

*

Aged green Chartreuse

*

Chartreuse has a very strong characteristic

taste. It is sweet, but it becomes spicy and sharp. You can certainly taste the herbs when you taste it, yet it is also balanced by sweetness; its aroma and flavor are of the

utmost complexity. According to many, at first taste, Chartreuse tastes very

much like its color – green (herbal/vegetal) – and it is very intense (110 proof!). If you combine

half jigger of Chartreuse with two jiggers of gin, your drink will still taste

like Chartreuse! Chartreuse has a mystifying

flavor that refuses to be conquered.

*

*

*

*

*

*

Your first whiff of Chartreuse may well leave

you dazed, confused, and captivated because you will smell dozens of plants/herbs,

which makes Chartreuse so deliciously intriguing. As is the case with other

liqueurs, the flavor is sensitive to temperature. If taken straight, it can be

served very cold, but is often served at room temperature (we assume that this

is how the monks drink it, and it is the most traditional way to drink it).

*

*

Chartreuse transitions in flavors and scents: a sweet licorice, peppermint, and pure black and white pepper notes can

be detected. Chartreuse is spicy without being harsh; it is sweet without

tasting like candy; and it is a blast of flavor, but never overwhelming. It is

always perfectly balanced. Chartreuse is certainly everything other liqueurs

try to be, but it stands alone as “the most

distinctive liqueur you can serve or give” and one that needs no matches,

chemicals, water, or sugar (as other liqueurs might). It is absolutely perfect just the way the Carthusian monks have always made

it!

*

*

*

*

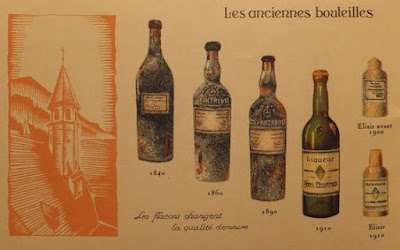

The Carthusian Order was more than 500 years

old when, in 1605 in Vauvert, a small suburb of Paris, the monks received a gift

from Francois Hannibal d’Estrées, Marshal of King’s Henri IV artillery: an

already ancient manuscript from an “Elixir” soon to be nicknamed “Elixir of Long Life.” This manuscript

detailed a blend, infusion, and maceration of 130 herbs, which was so complex

that only bits and pieces of it were understood and used. At the beginning of

the 18th century, the manuscript was sent to La Grande Chartreuse in Grenoble, where an exhaustive study of the

manuscript was undertaken by Frère Jerome Maubec who finally unraveled the

mystery.

Then, in 1737, a practical formula for the

preparation of the Elixir was drawn up. The distribution and sales of this new

medicine were limited. One of the monks of La

Grande Chartreuse, Frère Charles, would load his mule with the small

bottles that he sold in Grenoble and other nearby villages. Today, this “Elixir of Long Life” is still made only

by the Carthusian monks following that ancient recipe. This “liqueur of health” is all natural

plants, herbs and other botanicals suspended in wine alcohol – 69% alcohol by

volume, 138 proof. This elixir was so tasty that it was frequently used as a

beverage rather than as medicine, which led to the adaptation (in 1764) of the

ancient elixir recipe to make a milder beverage: this is what is known today as

“Green

Chartreuse” – 55% alcohol, 110 proof. The immediate success caused

the liqueur to be consumed far beyond the area around La Grande Chartreuse.

*

*

*

*

White Chartreuse

*

When the French Revolution erupted in 1789,

members of all Religious Orders were expelled, and the Carthusian monks were

forced to leave France in 1793. They made a copy of the manuscript kept by one

of them who remained in the Monastery, while another monk was in charge of the

original. This monk was arrested and sent to prison in Bordeaux, but fortunately

he was able secretly to pass the original manuscript to one of his friends, Dom

Basile Nantas. Dom Basile, convinced that the Order would never come back to

France and unable to make the Elixir himself, sold the recipe to Monsieur

Liotard, a pharmacist in Grenoble. Mr. Liotard never produced the Elixir. When

Monsieur Liotard died, his heirs returned the manuscript to the Carthusian

monks who had returned to their Monastery in 1816.

In 1838, the Chartreuse distillers developed a sweeter form of Chartreuse: “Yellow Chartreuse” (40% alcohol, 80 proof). In 1903, the French government nationalized the Chartreuse distillery and confiscated the monks’ property, expelling them again. This time, the monks, along with their secret recipe, went to Tarragona, Spain where they built a new distillery and began producing their liqueurs with the same label. However, an additional label said Liqueur fabriquée à Tarragone par les Pères Chartreux (“liquor manufactured in Tarragona by the Carthusian Fathers.” For eight years (from 1921 to 1929), the monks produced an additional liqueur in Marseille (France). The liqueur from Tarragona was nicknamed “Une Tarragone.” The one from Marseille was then officially called “Tarragone.”

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Summary:

*The gift of the manuscript in 1605

*The Elixir

Végétal (138 proof) finally made in 1737

*Green

Chartreuse (110 proof) in 1764

*Yellow Chartreuse (80 proof) in 1838

*A “White” Chartreuse (60 proof) between 1840

and 1880; then from 1886 to 1900

*After 1904, the liqueur made by the monks in

Tarragona nicknamed “Une Tarragone”

*V.E.P. (very prolonged aging) introduced in

1963

*The “Liqueur

du 9ème Centenaire” (94 proof) developed in 1984 to commemorate the 900th

anniversary of the foundation of the Carthusian Order

*The “1605” version (112 proof in 2005 to

commemorate the gift of the recipe by Marshall d’Estrées.

*The

“Liqueur des Meilleurs Ouvriers de France”

in 2007

* “Génépi”

(80 proof)

*

*

*

All of these liqueurs are made by the monks and

are based on that ancient manuscript from 1605. Only two monks are allowed to

know the names of the 130 herbs and plants used to make Chartreuse. Eighteen

tons of them are delivered to the Grande-Chartreuse Monastery every year. In

the “Herb Room,” the herbs and plants are dried, crushed, and mixed in

different series and are then kept in a bag carefully numbered and taken to the

distillery in Voiron. Each series of herbs and plants macerates in alcohol, and

each maceration is then distilled for about 8 hours.

Since the 19th century, the monks have used the

copper stills. Most of the distillation of the liqueurs today is done in the

stainless-steel stills, which have been designed especially for Chartreuse, in

order to enable a very accurate control of the distillation process and, just

as important, to allow the monks to monitor the distillation from the

Monastery, which is 15 miles away from the distillery.

*

*

*

*

*

Heated by steam, the alcohol and the essence of

the plants evaporate to the top of the swan neck, and then are cooled down in

the condenser becoming an alcoholate. A last maceration of plants gives its

color to the liqueur. A final control is made by the monks before the liqueur

can be put to age in the oak-casks of the maturing cellar. Built in 1860 and

enlarged in 1966 it is the largest liqueur cellar in the world: 164 meters

long. Chartreuse ages in oak casks from Russia, Hungary or France. After

several years, the monks will test the liqueur and decide if it is ready to be

bottled – only they can make this decision.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The sales of the liqueurs allow the Carthusians

the funds necessary to survive. The

fabrication of the liqueur Chartreuse is a great source of revenue and means of

support for the monks, and the surplus of their income is distributed in

charitable works.

*

*

*