So our Mass goes back, without essential change, to the age when it first developed out of the oldest liturgy of all. It is still redolent of that liturgy, of the days when Cæsar ruled the world and thought he could stamp out the faith of Christ, when our fathers met together before dawn and sang a hymn to Christ as to a God. The final result of our enquiry is that, in spite of unsolved problems, in spite of later changes, there is not in Christendom another rite so venerable as ours. ~Fortescue

Showing posts with label Latin Mass. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Latin Mass. Show all posts

Wednesday, December 18, 2019

Monday, November 18, 2019

Pilgrim Fatima Statue at Holy Innocents Church, NYC

Please note that there will be two (2) traditional Solemn Masses to celebrate such event.

*******

11:45 a.m. - Arrival of the Statue and Joyful Mysteries of the

Holy Rosary

12 noon – 1:30 p.m. - Confessions

12:15 & 1:15 p.m. - Holy Masses in English

2:00 p.m. - Exposition of the Most Blessed Sacrament and

Mysteries of Light

3:00 p.m. - Chaplet of Divine Mercy

4:00 p.m. - Sorrowful Mysteries of the Holy Rosary

5:00 p.m. - Glorious Mysteries of the Holy Rosary

4:45 p.m. – 5:35 p.m. - Confessions

6:00 p.m. - Solemn High Tridentine Votive Mass of the

Immaculate Heart of Mary followed by Outdoor Candlelight Procession of the Most Blessed Sacrament and Pilgrim Virgin Statue of Our Lady of Fatima

Night Vigil consisting of 20 Mysteries of the Most Holy Rosary and prayers of reparation to the Sacred

Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary

“Coffee Hour” and refreshments in

the Parish Hall

*******

A number of statues of Our Lady of Fatima have been carved by the Sanctuary in Portugal to travel throughout the world in order to spread Our Lady’s Peace Plan and Message of Fatima which is one of prayer, especially the prayer of the Holy Rosary, sacrifice and penance in reparation for sin, and Consecration to the Immaculate Heart of Mary through the Brown Scapular. The Archdiocese of New York is privileged to receive the sixth statue carved for this purpose. Having been carved decades ago, the Pilgrim Virgin which will be vising us has traveled the world many times over and has been venerated by countless Faithful.

Labels:

Catholic,

Catholic Church,

Fatima,

Holy Innocents Church,

Latin,

Latin Mass,

NYC,

Traditional Mass

Thursday, November 14, 2019

Indulgences

THE PROFIT OF INDULGENCES

The

question of Indulgences — their meaning, their value — suffers from a two-fold

disadvantage. To those outside the Church probably no Catholic dogma is

responsible for so much misunderstanding, the fruitful source of a theological

hatred that it would be hard to equal. The very name “indulgence” conjures up

to the Protestant imagination dark spectres of the past — Tetzel selling

barefaced licenses to commit, absolutions to pardon, every sin; the wealthy

salving their consciences by strips of parchment purchased by their gold; the

poor handing over their little all, with the credulity of superstition, to the

greedy vendors of spiritual wares, in the fond hope that Heaven’s gates will

open to their happy possessors; Luther, in “words that are half-battles,” denouncing

this hellish traffic in pardons that drowned men’s souls in perdition, as he

nailed to the church door at Wittenberg his thesis of defiance against a power

that professed to forgive sins without repentance of the sinner or amendment of

his life, and damned men’s souls while it promised to save them.

But even among Catholics, who know better than to be led astray by such distorted phantoms of the imagination, there is a tendency to put in the background, at least of thought, if not of devotional life, the whole subject of indulgences as an abstruse and almost esoteric part of the Christian belief, with little practical bearing on the everyday life of the soul. We have before now come across converts who told us that their instructors had assured them that, provided they gave their assent to the teaching of the Church of God on that particular point, they need not trouble their heads further about it. To all intents and purposes, it was relegated to an academic atmosphere, remote from the living circle of the great dogmas that mould the Catholic life from the cradle to the grave. This lack of true perspective can only arise from a want of consideration of what the Church actually teaches as regards indulgences. The difficulties that at first sight seem to enshroud the dogma with an impenetrable gloom, disappear almost imperceptibly when its real meaning and spiritual importance become apparent. For, in truth, no doctrine perhaps is more luminous in its bearing upon Catholic belief and conduct than that which links the Church of the twentieth century with the Church of the third and fourth centuries by an identical formula.

If it is the proud boast of the Catholic and Roman Church that she is semper eadem — teaching today what she taught at the beginning — an identity of type characterizing her doctrine (all development being from within, like the increase in stature of a growing child); this note of sameness is nowhere more prominent than in the doctrine, so much misunderstood and withal so fiercely attacked, of indulgences. The name itself should be sufficient to prove this; it brings us back to the early days of the Church’s history, when persecution tried the faith of her children, and discipline in reconciling the lapsed was correspondingly severe. Here is a confessor in prison, awaiting death for the love he bore to Christ — a love stronger than the ties of life; here is a poor sinner, perchance one who had been regarded as a light for his holiness, perchance a priest of the altar, who through cowardice had burnt a few grains of incense before a statue of the Emperor, and thereby perjured his soul. Remorse seizes him; he can have no peace until he has been reconciled to God and restored to the communion of the Church, which he had forfeited by his sin. What, then, does he do? He knows that he will have to undergo a lengthy penance before the Church will receive him, and he dreads the probation and the disgrace. So he goes to the holy confessor bound with chains in his dreary dungeon, and prays him to intercede in his stead, giving him a letter to present to the bishop in which to ask him, for the sake of his imprisonment and approaching death — in other words, through the application of his merits — to remove in whole or in part the canonical penalty which was the Church’s equivalent for the temporal punishment due to his sin of apostasy. And the bishop recognized the confessor’s plea, and, as the representative of the whole Christian Society, readmitted the penitent to the privileges of communion, without making him undergo the long months or years of penitential humiliation.

But even among Catholics, who know better than to be led astray by such distorted phantoms of the imagination, there is a tendency to put in the background, at least of thought, if not of devotional life, the whole subject of indulgences as an abstruse and almost esoteric part of the Christian belief, with little practical bearing on the everyday life of the soul. We have before now come across converts who told us that their instructors had assured them that, provided they gave their assent to the teaching of the Church of God on that particular point, they need not trouble their heads further about it. To all intents and purposes, it was relegated to an academic atmosphere, remote from the living circle of the great dogmas that mould the Catholic life from the cradle to the grave. This lack of true perspective can only arise from a want of consideration of what the Church actually teaches as regards indulgences. The difficulties that at first sight seem to enshroud the dogma with an impenetrable gloom, disappear almost imperceptibly when its real meaning and spiritual importance become apparent. For, in truth, no doctrine perhaps is more luminous in its bearing upon Catholic belief and conduct than that which links the Church of the twentieth century with the Church of the third and fourth centuries by an identical formula.

If it is the proud boast of the Catholic and Roman Church that she is semper eadem — teaching today what she taught at the beginning — an identity of type characterizing her doctrine (all development being from within, like the increase in stature of a growing child); this note of sameness is nowhere more prominent than in the doctrine, so much misunderstood and withal so fiercely attacked, of indulgences. The name itself should be sufficient to prove this; it brings us back to the early days of the Church’s history, when persecution tried the faith of her children, and discipline in reconciling the lapsed was correspondingly severe. Here is a confessor in prison, awaiting death for the love he bore to Christ — a love stronger than the ties of life; here is a poor sinner, perchance one who had been regarded as a light for his holiness, perchance a priest of the altar, who through cowardice had burnt a few grains of incense before a statue of the Emperor, and thereby perjured his soul. Remorse seizes him; he can have no peace until he has been reconciled to God and restored to the communion of the Church, which he had forfeited by his sin. What, then, does he do? He knows that he will have to undergo a lengthy penance before the Church will receive him, and he dreads the probation and the disgrace. So he goes to the holy confessor bound with chains in his dreary dungeon, and prays him to intercede in his stead, giving him a letter to present to the bishop in which to ask him, for the sake of his imprisonment and approaching death — in other words, through the application of his merits — to remove in whole or in part the canonical penalty which was the Church’s equivalent for the temporal punishment due to his sin of apostasy. And the bishop recognized the confessor’s plea, and, as the representative of the whole Christian Society, readmitted the penitent to the privileges of communion, without making him undergo the long months or years of penitential humiliation.

There

we have in a nutshell the full doctrine of indulgences. The Communion of Saints;

the belief that what one member of the body does is shared by all the other

members, or, as St. Paul expresses it, “If one member glory, all the members

rejoice with it;” the application, by

virtue of that vital fellowship, of the merits, whether of the Head, Christ

Jesus, or of His saints (for the confessor in his dungeon, or the martyr

burning in the cruel flame, could have no merit apart from the Lord, to whom

they were united by the joints and bands of divine grace), to the penitent

sinner for the remission of the temporal punishment due to his sin, represented

by the canonical penance, whose only raison d’etre was the Church’s

conviction that by it the temporal penalty could be expiated; these three

elements of an indulgence were as much present in the days of Tertullian and

St. Cyprian in the third century, as in those of Leo XIII in the twentieth. For

by an indulgence the Church teaches to-day the identical doctrine that she

taught then. She claims now, as in the days of persecution, the power of

remitting, in whole or in part, the debt of temporal punishment for sin (or its

substitute in the canonical penalty imposed by the Church in satisfaction to

God), that survives after its guilt and eternal punishment have been forgiven;

— and this by the application of the merits of Christ and His saints. Even at the

present day, after some 1600 years, the Catholic Church uses the same language

in her indulgences. When we read of 100 days’, 200 days’, 300 days’ indulgence,

our memory is perforce recalled to the time when canonical penance, lasting for

various lengths of time, was wont to be exacted from the excommunicated seeking

reconciliation. The indulgence corresponds to the canonical penance, being

substituted for it even in the amount of the temporal chastisement which is

remitted by it.

But the doctrine of indulgences is not only a support to faith, in that it is a striking witness to the purity of the Catholic faith, which remains unchanged, in spite of all the fluctuations of time; it has also a distinct place of importance in the spiritual life of conflict against temptation and sin. As defined by theologians, an indulgence is declared to be “the remission of temporal punishment still due from the sinner after the guilt of his sin has been washed away, — which remission is binding at the tribunal of God in heaven, since its force lies in the application of the treasure of the Church made by a lawful superior.” To understand fully the spiritual benefits conferred by an indulgence it is necessary to consider the precise meaning of that “temporal,” or non-eternal, “punishment” which is cancelled by the application of the merits stored in the treasure-house of the Catholic Church.

But the doctrine of indulgences is not only a support to faith, in that it is a striking witness to the purity of the Catholic faith, which remains unchanged, in spite of all the fluctuations of time; it has also a distinct place of importance in the spiritual life of conflict against temptation and sin. As defined by theologians, an indulgence is declared to be “the remission of temporal punishment still due from the sinner after the guilt of his sin has been washed away, — which remission is binding at the tribunal of God in heaven, since its force lies in the application of the treasure of the Church made by a lawful superior.” To understand fully the spiritual benefits conferred by an indulgence it is necessary to consider the precise meaning of that “temporal,” or non-eternal, “punishment” which is cancelled by the application of the merits stored in the treasure-house of the Catholic Church.

Every

sin committed has a two-fold effect: it stains the soul with guilt, and it

leaves behind it a severe penalty of pain. It need scarcely be said that an

indulgence is only concerned with the latter consequence. The stain of crime

cannot be washed away by anything short of the Blood of Jesus Christ: it needed

the death of God to destroy the mark of sin stamped on the sinner’s soul. No

indulgence can purge the foulness of the smallest sin. The sinner must find

peace through the way of penitence, by the strength of an abiding contrition.

An indulgence is valueless unless its recipient is united by grace to Christ,

from whom the merits on which it rests flow to every member of His Body. It is

only granted to those who are already reconciled to God — the stain of their

sin washed away, their souls purified, by the cleansing waters of Baptism, by

the fire of perfect contrition, or by the application of the Precious Blood in

the Sacrament of Penance.

It is true that sometimes in ancient forms of indulgences we find reference made to the forgiveness of sins, e.g., “Concedimus indulgentiam omnium peccatorum;” “Relaxamus tertiam partem peccatorum;” “Absolvimus a culpa et a poena,” etc. But in the first place, it must be remembered that we have Scriptural authority for including the punishment due to sin under the general term “sin,” as, e. g., in I Peter 2 : 24, “Who (Himself) bore our sins in His body upon the tree;” — so that the true meaning of the words in question is, “We relax or grant indulgence for the whole temporal punishment still to be expiated for sins committed and pardoned ... or for its third part.” In the second place, if, as we have seen, sacramental confession is the usual prerequisite condition for an indulgence to be gained, it is plain that both the culpa and the poena — the guilt and the pain of sin — are remitted by indulgences: the one indirectly by previous confession and absolution (or by an act of contrition), the other directly by the bestowal of the indulgence.

But apart altogether from the blot of guilt that stains the immaculate purity of the soul, each sin entails a penalty, rivets a fetter of pain upon the sinner, which he has to bear in order to satisfy the just demands of the outraged majesty of God. The guilt, the crime, the culpa of sin is not touched by the grant of any indulgence, however great; but the punishment, the temporal effect of sin still remaining to be expiated, after the sin itself has been forgiven and its eternal punishment escaped, — this secondary consequence can be remitted wholly or partially by the officers of Christ’s Church — the Supreme Pontiff (the successor of him to whom the promise was made, “Whatsoever thou shalt loose upon earth shall be loosed also in heaven”) and the bishops throughout the world in communion with him who can echo the words of St. Paul, “What we have pardoned for your sakes we have done it in the person of Christ.”

This temporal punishment which survives the forgiveness of the actual sin is manifold. It comprises such effects of transgression as loss of money, of friends, of one’s good name; disease of body, failure of mental power, remorse of soul, destroying, like a canker worm, all happiness and peace. It enters even into the sphere of the after-life. Punishment unexpiated here has to be undergone in purgatory, where the “penal waters” finally obliterate the last traces of sinful rebellion. But more terrible, because spiritual in their consequences, than these obvious results of sin, are the evil habits contracted, the links of the long chain of evil influences, that weigh down and hold back the penitent, as he tries painfully to rise after his sad and disgraceful fall. Each separate act of sin tends to make resistance to the temptation more difficult. The habit formed does not vanish with the forgiven sin; it abides with us as a reminder of our ingratitude, a mute witness to the awful sanctity of God whose law we have so lightly set at naught.

This branch of temporal punishment is often lost sight of, although its bearing on the spiritual profit of indulgences makes it of the utmost importance. An indulgence is too often regarded as a mechanical balancing of the books, so that the credit side of the soul's account with God may equal the debit, whereas it positively aids us in our struggle against sin. It only needs for us to look into ourselves to realize the fact of the advantage to be gained by a greater or less freedom from the thralldom of evil memories, evil propensities, which sinful actions inevitably bear in their train as by a natural law. The guilt of our sin has been destroyed; the absolving words said over us, and we have felt to the centre of our being that we have been truly forgiven by God. And yet in spite of this, we are sadly conscious that our life is different from what it was before we sinned. Sin has thrown its bewitching glamor around us, and once having yielded to its fatal charm we find it hard to resist when it allures us a second time.

Taken from The Dolphin, Vol. 1, 1902

It is true that sometimes in ancient forms of indulgences we find reference made to the forgiveness of sins, e.g., “Concedimus indulgentiam omnium peccatorum;” “Relaxamus tertiam partem peccatorum;” “Absolvimus a culpa et a poena,” etc. But in the first place, it must be remembered that we have Scriptural authority for including the punishment due to sin under the general term “sin,” as, e. g., in I Peter 2 : 24, “Who (Himself) bore our sins in His body upon the tree;” — so that the true meaning of the words in question is, “We relax or grant indulgence for the whole temporal punishment still to be expiated for sins committed and pardoned ... or for its third part.” In the second place, if, as we have seen, sacramental confession is the usual prerequisite condition for an indulgence to be gained, it is plain that both the culpa and the poena — the guilt and the pain of sin — are remitted by indulgences: the one indirectly by previous confession and absolution (or by an act of contrition), the other directly by the bestowal of the indulgence.

But apart altogether from the blot of guilt that stains the immaculate purity of the soul, each sin entails a penalty, rivets a fetter of pain upon the sinner, which he has to bear in order to satisfy the just demands of the outraged majesty of God. The guilt, the crime, the culpa of sin is not touched by the grant of any indulgence, however great; but the punishment, the temporal effect of sin still remaining to be expiated, after the sin itself has been forgiven and its eternal punishment escaped, — this secondary consequence can be remitted wholly or partially by the officers of Christ’s Church — the Supreme Pontiff (the successor of him to whom the promise was made, “Whatsoever thou shalt loose upon earth shall be loosed also in heaven”) and the bishops throughout the world in communion with him who can echo the words of St. Paul, “What we have pardoned for your sakes we have done it in the person of Christ.”

This temporal punishment which survives the forgiveness of the actual sin is manifold. It comprises such effects of transgression as loss of money, of friends, of one’s good name; disease of body, failure of mental power, remorse of soul, destroying, like a canker worm, all happiness and peace. It enters even into the sphere of the after-life. Punishment unexpiated here has to be undergone in purgatory, where the “penal waters” finally obliterate the last traces of sinful rebellion. But more terrible, because spiritual in their consequences, than these obvious results of sin, are the evil habits contracted, the links of the long chain of evil influences, that weigh down and hold back the penitent, as he tries painfully to rise after his sad and disgraceful fall. Each separate act of sin tends to make resistance to the temptation more difficult. The habit formed does not vanish with the forgiven sin; it abides with us as a reminder of our ingratitude, a mute witness to the awful sanctity of God whose law we have so lightly set at naught.

This branch of temporal punishment is often lost sight of, although its bearing on the spiritual profit of indulgences makes it of the utmost importance. An indulgence is too often regarded as a mechanical balancing of the books, so that the credit side of the soul's account with God may equal the debit, whereas it positively aids us in our struggle against sin. It only needs for us to look into ourselves to realize the fact of the advantage to be gained by a greater or less freedom from the thralldom of evil memories, evil propensities, which sinful actions inevitably bear in their train as by a natural law. The guilt of our sin has been destroyed; the absolving words said over us, and we have felt to the centre of our being that we have been truly forgiven by God. And yet in spite of this, we are sadly conscious that our life is different from what it was before we sinned. Sin has thrown its bewitching glamor around us, and once having yielded to its fatal charm we find it hard to resist when it allures us a second time.

Experience

corroborates this truth. Can the sensualist who has for years given over his

body to every lustful disordered passion, turn over a new leaf at once in spite

of his weakened body, enfeebled mind, perverted will, and live in innocent

purity as in the far-off days of his happy childhood? Can the besotted

drunkard, who has tasted the delights of wild confused pleasure, be the same man

after he has signed the pledge as he was before he first yielded to the

temptation, and drank to his ruin the fruit of the grape?

We know that such is not the case. As we have sown, so do we reap. Each sin bears its fruit as surely as the tree its blossoms. The evil habits contracted in youth, of carelessness, sloth, self-indulgence, undisciplined speech, unbridled desire — habits that increase in our riper years — are hardly broken. Our sins may be blotted out, but their chastisement remains. We carry ever about with us a diseased imagination, a knowledge of evil, penetrating our every thought, from which we cannot shake ourselves free. The weight of the heavy chains of evil habit and inclination, forged by us so tightly when we sinned, bows us down to this lower earth, keeping us back from spiritual progress.

It is to destroy this secondary effect of sin, this accumulation of evil habits, this temporal penalty in its many ramifications, that indulgences are granted us by the Church. The sinner must pay the debt of punishment, or another must pay it in his stead. In the Catholic Church, as in some palace of kings, there is a treasury wherein is contained wealth, infinite, inexhaustible — even the satisfactions of Christ and the super-abounding merits of His saints. This boundless sea of satisfaction can be applied to individual members of the Body of Christ, because they are His members — bone of His bone, flesh of His flesh — and the power and virtue flowing from the Head reaches to each least part of the organism vitally united to Him. And this application of indulgences cancels the debt, unloosens the bands of the sinner’s pain, and sets him free from the captivity of evil. The evil habit that cloaks the soul, driving out the air and sunshine of every holy impulse; the heavy chain that clanks drearily as the sinner tries to enter the house of peace; the searching punishment that falls with heavy weight upon his shoulders; the temporal misfortunes that God’s sanctity demands in reparation for repeated acts of rebellion — all are set aside by the gracious act of the Redeemer Who from the Cross granted the first indulgence to the penitent thief: “Today shalt thou, freed by My royal word from every bond of sin, today shalt thou be with Me in Paradise.”

Thus, an indulgence is of real advantage to the soul. If it is no relic of a far-distant past, possessing only an antiquarian interest, but an important witness to the identity of the Catholic Faith of the twentieth century with that of the primitive age, it is doubly true that besides its evidential value, it is of solid profit to us in the spiritual life of toil and battle. Each indulgence that we gain releases us from the effects of sin — effects that hinder us in our struggles against evil —, strengthens our resolutions, and brings us nearer to God. We cannot see here the full extent of the benefits thereby conferred upon us. We can only know from inward experience how the seductions of sin become less powerful, the influence of evil habit decreases, the sad memories of past falls fade away, presaging the glad day when, through the virtue of indulgences powerful even beyond the veil, we enter the gates of the City of everlasting peace.

We know that such is not the case. As we have sown, so do we reap. Each sin bears its fruit as surely as the tree its blossoms. The evil habits contracted in youth, of carelessness, sloth, self-indulgence, undisciplined speech, unbridled desire — habits that increase in our riper years — are hardly broken. Our sins may be blotted out, but their chastisement remains. We carry ever about with us a diseased imagination, a knowledge of evil, penetrating our every thought, from which we cannot shake ourselves free. The weight of the heavy chains of evil habit and inclination, forged by us so tightly when we sinned, bows us down to this lower earth, keeping us back from spiritual progress.

It is to destroy this secondary effect of sin, this accumulation of evil habits, this temporal penalty in its many ramifications, that indulgences are granted us by the Church. The sinner must pay the debt of punishment, or another must pay it in his stead. In the Catholic Church, as in some palace of kings, there is a treasury wherein is contained wealth, infinite, inexhaustible — even the satisfactions of Christ and the super-abounding merits of His saints. This boundless sea of satisfaction can be applied to individual members of the Body of Christ, because they are His members — bone of His bone, flesh of His flesh — and the power and virtue flowing from the Head reaches to each least part of the organism vitally united to Him. And this application of indulgences cancels the debt, unloosens the bands of the sinner’s pain, and sets him free from the captivity of evil. The evil habit that cloaks the soul, driving out the air and sunshine of every holy impulse; the heavy chain that clanks drearily as the sinner tries to enter the house of peace; the searching punishment that falls with heavy weight upon his shoulders; the temporal misfortunes that God’s sanctity demands in reparation for repeated acts of rebellion — all are set aside by the gracious act of the Redeemer Who from the Cross granted the first indulgence to the penitent thief: “Today shalt thou, freed by My royal word from every bond of sin, today shalt thou be with Me in Paradise.”

Thus, an indulgence is of real advantage to the soul. If it is no relic of a far-distant past, possessing only an antiquarian interest, but an important witness to the identity of the Catholic Faith of the twentieth century with that of the primitive age, it is doubly true that besides its evidential value, it is of solid profit to us in the spiritual life of toil and battle. Each indulgence that we gain releases us from the effects of sin — effects that hinder us in our struggles against evil —, strengthens our resolutions, and brings us nearer to God. We cannot see here the full extent of the benefits thereby conferred upon us. We can only know from inward experience how the seductions of sin become less powerful, the influence of evil habit decreases, the sad memories of past falls fade away, presaging the glad day when, through the virtue of indulgences powerful even beyond the veil, we enter the gates of the City of everlasting peace.

W.

R. Carson.

Shefford, England

Labels:

Catholic Church,

Confession,

Credo,

Forgiveness,

Indulgences,

Indulgentia,

Latin Mass,

Saints,

Traditional Mass

Thursday, October 10, 2019

What difference does it make?

What difference

does it make?

Recently, Pope Francis, was “pained to hear… a sarcastic comment about a

pious [indigenous] man with feathers on his head who brought an offering”

during Mass. In humble solidarity with the “pious

man,” His Holiness asked: “Tell me: what’s the difference between having

feathers on your head and the three-peaked hat worn by certain officials in our

dicasteries?” The Supreme Pontiff was referring to the Catholic biretta.

Apparently, to the Apostolic Lord of Rome, these types of things make no

difference whatsoever.

But we ask ourselves, how come His Supreme

Humbleness was “pained to hear” such

comment, but did not feel the same pain when His Holiness Himself made some

disparaging remarks about young “rigid”

priests who wear Cassocks and the Roman hat (“saturno”)? How quickly His Holiness’ pain disappears when those who

don’t agree with all that comes out of His Merciful Mouth are the ones who are

viciously offended, vindictively attacked, and savagely persecuted by His

Holiness Himself or His Holiness’ protégés!

How far is the reigning Pontiff from the

example of Pope St. Gregory I when writing to Eulogius of Alexandria: “My honor is the honour of the Universal

Church. My honor is the firm position of my brothers. I am really honoured when

due honor is not denied to each of them.” Instead, Pope Francis has a

preference for attacking, ridiculing, and disparaging whatever may bring

visibility to anything that used to bring honor and respect to the Church of

God, Her faithful ministers, and Her immemorial practices.

Our “Catholic sensibilities” are not supposed

to be hurt by such things, the reasoning goes, or by horrible pagan-like/shamanic ceremonies at the Vatican in the presence of the Pope

Himself! According to this logic, what

difference does it make to see practices and ceremonies that predate the

advent of Christianity performed with the consent and approval of the visible

Head of the Catholic Church? It would seem that to His Holiness they are the

same as the ceremonies of the Mass – the New Mass, that is, because WE KNOW how His Holiness feels about

the Old Mass! WE KNOW that those old

immemorial rites, practices, and ceremonies of the Roman Church do make a

difference to His Humble Person! So much so, that His Holiness and His

Holiness’ friends are willing to lie, persecute, slander, and stamp out

anything reminiscent of the old Catholic days… Such “rigidly neopelagian promethean observances that cause deeply-rooted

psychological problems” should have no place in the Church of God! Or so is

their humble wish.

We could get the impression that, according to

His Holiness, the way we feel about Holy Mass is the same way we should feel

about ritualistic services to Pachamama

(mother earth) with representations of Yacy,

Ruda, and Guaracy – all pure and unadulterated

pagan idolatry and immodesty ....

this should make no difference at all, they say. Just as it would make

no difference to His Holiness and minions if what had taken place had been the

burning of incense –or, better yet, the killing of babies!– in honor of the

ancient golden calf idolized by the Hebrews after the God of Israel freed them

from the hands of Pharaoh.

At the (“fertility ritual”) ceremony that took

place in the Vatican gardens on October 4th in honor of Pachamana, the Holy Father was given a black ring (tucum ring – anel de tucum), which has become very closely associated with the

principles of Liberation Theology,

which in the Pontificate of Pope Francis has reached levels of biblical

importance. With regards to the ceremony, Cardinal Baldisseri said: “the purpose is to focus on this garden [the Amazon region] of immense

wealth and natural resources… and a territory that’s threatened by the runaway

ambitions of human beings rather than being taken care of.”

Honestly, that whole thing reminded us of another Garden (spoken of in the first

book of the Sacred Scriptures) where those involved had the ambition to be like

gods, and we all know that that led to negative consequences of unparalleled

proportions. And here we are in 2019 with high ranking members of the Catholic

Church (the Bishop in white included) tempting the same God with a similar

ambition and behaving as if the Incarnation of the Son of God had never

happened. How horrible is that! And

then today we hear that the Holy Father’s friend, the “journalist” Eugenio

Scalfari (a Leftist atheist), reports that the Holy Father told him that Christ

was not God. We’re not sure about you, but that’s flirting directly with

Sabellianism, Arianism, Modalism, Patripassianism, Subordinationism,

Nestorianism, and a few other officially certified heresies… nothing new about

the heresy, except that the One Who might possibly be dishing it out is none

other than the Supreme Pontiff Himself!

In the old days of Faith, the Popes would have

been the ones to clarify the correct teaching the faithful were to hold, but

that does not seem to be the case these days. Pope Julius, in the times of St.

Athanasius, during the Arian heresy, would have said: “Do you not know that this is the custom, that you should write first to

Us and that what is right should be settled here?” Pope St. Agatho would

have said: “The Apostolic [Roman] Church

of Christ, by the grace of Almighty God will never be shown to have wandered

from the path of Apostolic tradition, nor has it ever fallen into heretical

novelties; but it was founded spotless at the time of the beginning of the

Christian faith.” It might be safe to say, and I think you will agree, that

Francis the Merciful would cut His Humble tongue out before saying anything

like that! Instead, His Holiness would yell at us and at the top of His

Apostolic lungs –oops, we forgot His Holiness only has one, though that does

not prevent His Holiness from yelling at us anyway!– what’s the difference?

Well, to us, faithful Catholics, it does make a

big difference... just as one “iota”

made an essential difference in the 4th century with the Arian heresy. As Fr.

Adrian Fortescue aptly said: “What, it is

asked, can the difference between Homoüsios and Homoiüsios matter? Was it worth

while to rend the whole Church for the sake of an iota? Undoubtedly to a person

who cares nothing for any dogmatic belief, to whom the Christian faith means

either nothing at all or a vague humanitarianism, the discussion will seem

absurd… But to people who take historic Christianity seriously one may point

out that the question at issue was the vital one of all. It was that of the Divinity of Christ.”

And Fr. Fortescue goes on to say that in

combat, soldiers from two different sides whose nations have very similar flags

“or [coats of] arms” would not waver in their allegiance to their nation

because of such similarity or very slight differences. So, while for the

Servant of the Servants of God an indigenous feathered hat might be the same as

a biretta, to an actual faithful Catholic, there is a real difference between

the two. Just as an actual Catholic will detect a clear difference between real inculturation and neo-paganization!

The Supreme Pontiff may go on and on with all

this silly stuff about “pockets of rigidity” and “semi-schismatic ways” that

lead to a bad end and to an “unhealthy view of the Gospel,” but the thing is

that we somehow still have something called the Ten Commandments. And the first of these commandments still reads:

“I

am the Lord thy God, Who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the

house of bondage. Thou shalt not have strange gods before Me.” Actual

faithful Catholics, despite the criticisms and condemnations coming from

Bishops, Cardinals, and the Holy Father Himself these days, still want to

continue the ancient Catholic practice of worshiping the True God alone by

preserving the purity and integrity of the Catholic Faith through absolute

loyalty to the Church of Old Rome in Her unchanging dogmas and living

traditions, particularly in the true Roman Mass.

The Holy Father also thinks that these rigid

neo-palagians want “to change the Pope” by expressing open criticisms that

create, according to His Holiness, “confusion” and “division” and “schism.” As

Archbishop Lefebvre once said: “I don’t

want to disobey the Pope, but he must not ask me to become Protestant,” except that now that would have to be changed to:

“I don’t want to disobey the Pope, but he

must not ask me to become Pagan.”

That seems to be the difference between Paul VI and Pope Francis; the former

wanted to protestantize things, but the latter is hellbent on paganizing

everything! In response, we could say what Princess Pallavicini said in the

1970s when Paul VI’s Vatican tried to pressure her into not helping Archbishop

Lefebvre: “I am a more than convinced

Apostolic Roman Catholic … I owe nothing to anybody, I have no honours nor

prebends to defend, and I thank God for everything. Within the limits that the

Church allows, I may dissent, I may talk, I may act: I have to talk and I have

to act: it would be cowardice not to. And allow me say, that in our home, also

in this generation, there is no room for the cowardly.”

Long gone are the days when Popes, like St. Leo

the Great, would write to world leaders: “…

the same Faith must be that of the people, of bishops, and also of kings, oh

most glorious son and most clement Augustus!” Or Popes like Leo IX, writing

to the heretic Michael Cerularius on the preservation of Church unity: “… Woe to those who break it! Woe to those

who ‘with high-sounding and false words and with impious and sacrilegious hands

cruelly try to rend the glorious robe of Christ, that has no stain nor spot.’”

And, as the same Pope Leo IX wrote to the then ambitious Patriarch of

Constantinople: “Let heresies and schisms

cease. Let every one who glories in the Christian name cease from cursing and

wounding the holy Apostolic Roman Church.” And this was, as it should

always be, the case because it is the constant Catholic principle that there MUST NOT BE ANY COMPROMISE in

matters of Faith and Morals. Unfortunately, and with utmost sadness and

shame, it must be admitted that even faithful Catholics these days fall short

of this essential Catholic principle…

Nevertheless, we’ll continue to pray for our

Beloved Pope Francis, despite His Holiness’ love of deception, schism,

division, confusion, heresy, scandal, perversion, etc., which will be to His

Holiness’ eternal disgrace if no change takes place in His Humble and Merciful

Heart before His Holiness meets the Supreme Judge of all. And we, faithful

Catholics, must continue with our daily living as Catholics did in the old

Catholic days, when Rome was unequivocally “the

center and organ of unity,” when Rome’s guidance was “known, respected, and universally accepted.” This current trend of

exchanging the teachings of Christ for communist ideas, corruption of morals,

and pagan practices does not sit well with us … given that we keep in mind

constantly what Galatians 6:7 tells us: “Be

not deceived, God is not mocked.”

What an interesting

Pontificate this is!

Wednesday, August 21, 2019

The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass

Introduction

to "The Sacred Ceremonies of Low Mass"

By

Rev. Felix Zualdi, CM

The

august Sacrifice of the Mass comprises in itself all that is most sublime and

sacred in our Holy Religion. All the sacrifices of the Old Testament were only

shadows of that of the new, which, as St. Leo says, really offers to God what

the Jewish sacrifices only promised. The offering should bear some proportion

to the person to whom it is made; but since the ancient sacrifices were only

weak and needy elements, they could in no way satisfy for man’s debts to God

and hence another sacrifice was required. The old victims were insufficient,

the Levitical priesthood was impotent in the sight of God, therefore it was

necessary, as the Fathers of the Council of Trent express it, that by the

ordination of God the Father of Mercies, another Priest, according to the order

of Melchisedech, our Lord Jesus Christ, should arise, who would consummate and

bring to perfection all who were to be sanctified. Although Our Lord fully

consummated the sacrifice by offering Himself to God the Father, and by dying

on the altar of the Cross for our redemption yet His priesthood was not to

expire with His death, but was to continue visible in His Church to the end of

ages, as He Himself promised at His Last Supper when, instituting the

Eucharistic Sacrifice, He gave the same Divine authority to the Apostles and to

their successors. Every Priest can, therefore, say to himself when ascending the

altar: I am no longer a mere man of clay, a weak creature—being identified with

Jesus Christ through the power and the infinite value of the Victim I am about

to offer. With what a high degree of virtue ought such a dignity be

accompanied!

There

are four kinds of worship given to God in the Sacrifice of the Mass. The first

is called Latreutic, which is due to Him and can be given to His Infinite

Majesty alone, and which is rendered by the Sacred Victim along with the

adoration of the faithful, of the Saints, and of the Angelic Hosts, who,

according to the opinion of the Fathers, reverently surround the altar. The

second form of worship is termed Eucharistic, by which man raises his

voice in perfect thanksgiving to his most generous Benefactor. In it, the

excess of the Divine Goodness invests us with the power of offering abundant

satisfaction to Him; and the greatest advantage we derive from this benefit is,

that we can thereby make an adequate return for what we have received from God.

God delivers us from the abyss; we present to Him the Deliverer. He opens

Heaven to us; we offer to Him the Heir. So much does the supreme goodness shine

forth in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, that not only is our act of

thanksgiving in keeping with the great benefits conferred upon us, but forms a

return in some way suitable for the great love manifested in His conferring them

upon us. We do this not merely once, as St. Gregory Nazianzen remarks, as when

our Blessed Lord offered Himself in the Incarnation to His Eternal Father, but

a thousand times, when we offer that Divine Son in the Mass, impassible and

glorious as a worthy victim of thanksgiving.

The third act of worship

is Propitiatory—to appease

the anger of God, to satisfy the demands of His justice, and to obtain the

pardon of our sins. Man should appease the Lord to whom he has been ungrateful,

and avert His anger lest he might be cast off forever. All other creatures

cried for vengeance against sinful man: Jesus Christ appeared and immolated

Himself upon the Cross; peace came upon the world, man’s sins notwithstanding,

and the unbloody Sacrifice of the Mass pours out on him the grace of repentance

and reconciles him with Divine justice. The Sacrifice of Calvary supplied the

treasures, that of the Mass distributes them. From the treasury, judge of the key;

and if the Passion of Jesus Christ fits us for the benefits of Redemption, the

Sacrifice of the Mass enables us to enjoy them, for St. Chrysostom says : “Tantum valet celebratio Missae quantum mors

Christi in cruce,” and the Church herself moreover assures us of it in

these words: “Quoties hujus hostiae

commemoratio celebratur, opus nostrae Redemptionis exercetur.”

But

the worship we render to God, as the Author of every good gift, is based upon

our prayers, serving as we do a Lord who wishes us to pray to Him, uniting His own

glory with our best interests. “Call upon

Me,” He says, “in the day of trouble;

I will deliver thee, and thou shalt glorify Me.” Prayer constitutes the

fourth act of worship, called Impetratory, for the due rendering of which

to God the Mass furnishes us with the best of all means of moving the Divine

liberality in our favour. We are unworthy not only to be heard but even to ask,

and consequently unworthy of receiving, from the very fact that we are obliged

to ask. The Word of God prayed for us, and “was

heard for His reverence.” In the Mass He prays to the Father continually

for us, in the same manner as He did, bathed with tears and blood, on the

Cross, and we through Him are heard. On the altar the word of Salvation is

raised, the life-giving Host is laid, and there is worked the most sublime

miracle, ravishing in ecstasy of wonder earth and heaven. The Son of God, the

invisible High Priest, the Holy Pontiff, just, innocent, separated from

sinners, higher than the heavens, and able to compassionate us in our

infirmities, intercedes for us with unutterable groanings, and becomes our propitiation,

our victim: and the Eternal Father, who promised to hear everyone invoking Him

in the name of His Son, cannot refuse the Son Himself praying, and offering

Himself for us. “O Father!” we may

suppose Him to exclaim in the Mass, “O

Father! wilt Thou not remember the sacrifice which I consummated on Calvary? Look

down on the renewal of it, that Thou mayst bestow on My brethren the graces I

gained by My death.”

Such is the excellence of

the sacrifice of our altars. Would to Heaven that all the Priests going forth

every day with joy to the mystic Calvary, animated with sublime sentiments of

religion, and covered with the blood of Our Redeemer, would present themselves

to the Father, uniting, as St. Gregory the Great remarks, by an interior and

invisible sacrifice, their groans to those of the Victim who died for men, and

showing themselves alive to their solemn office and to the wants of poor souls.

Then would they, by the Mass, honour the majesty of God, thank Him for His

benefits, appease His justice, and implore His mercy. And since of all our

functions, the Mass is the most holy and the most divine, fulfilling, as it

does, the four great

ends already mentioned, it appears very clear that no study or diligence should

be omitted by the Priest in order that such a sacrifice may be celebrated with

the greatest possible interior purity and exterior devotion, as the Council of

Trent directs, declaring that the terrible anathemas fulminated by the Prophet

against those who perform negligently the functions prescribed for divine worship

apply rigidly to the ministers who celebrate Mass with irreverence. In order

then that the Priest may avoid so great a fault, and the divine malediction

consequent on it, let us remind him in the Introduction to this work what he

ought to do before celebrating, while celebrating, and after having celebrated.

All may be reduced to these three points: 1st, Preparation; 2nd,

Reverence and Exactness; 3rd, Thanksgiving.

1. The Preparation is

remote and immediate; the remote consists in the pure and virtuous life, which

should be led by the Priest, in order that he may celebrate worthily.

Therefore, his acts, his words, his thoughts should breathe of purity, that he

may be fit to celebrate with proper dispositions. If he who handled the sacred vessels

of old should be pure, how much more so must the Priest be, who bears in his

hands and in his breast the Incarnate Word of God? This purity of life

consists, first, in preserving himself undefiled from every sin, not only

mortal, as he is necessarily bound to—but also, to secure greater purity, every

deliberate venial sin, and even from every affection to venial sin; and

secondly, it consists in applying himself most diligently and constantly to the

acquisition of every virtue. “Qui justus est, justificetur adhuc, et sanctus, sanctificetur adhuc”

(Apoc. xxii. ii). For

the immediate preparation, mental prayer is requisite. The venerable John of

Avila prescribes an hour and a half; St. Alphonsus reduces the time of

immediate preparation to half an hour, and even to a quarter; but he adds,

indeed, a quarter of an hour is too little. The Passion of Jesus Christ should

be the continual thought of the Priest. Having finished his meditation it is

meet he should recollect himself for some time before proceeding to celebrate,

and consider the great action he is about to perform. He should seriously

ponder, says St. Augustine, these four thoughts: “Cui offeratur, a quo offeratur, quid offeratur, pro quibus offeratur.”

On entering the sacristy, he should say with St. Bernard: “Worldly affections and solicitudes, wait here until I have celebrated

Mass.” The Priest should likewise consider that he is about to call from

heaven to earth the Word Incarnate, to sacrifice Him anew to the eternal Father,

to be fed with His sacred flesh; he should in fine, reflect upon his most

serious responsibility in becoming at the altar the mediator between God and

man.

2. Reverence and

Exactness.—It is necessary in celebrating, to manifest all the reverence

due to so great a sacrifice. This reverence means that due attention be paid to

the words of the Mass, and that all the ceremonies prescribed by the Rubrics be

exactly observed. As to the attention, the Priest sins by willful distractions

while saying Mass; and these willful distractions, if occurring at the

consecration of the sacred species, or during a notable portion of the Canon

are, according to a large body of theologians, mortal sins. It is not

considered possible that a Priest so acting could fulfil what is prescribed by

the Rubric in these words: “Sacerdos

maxime curare debet ut . . . distincte et apposite proferat . . . non admodum

festinanter, ut advertere possit quae legit.” Exactness regards the

fulfilment of the ceremonies enjoined by the Rubrics, in the celebration of the

Divine Sacrifice. The Bull of St. Pius V., found in the beginning of the

Missal, strictly commands that the Mass be celebrated according to the rite of

the Missal, so that no willful omission, even though it be trivial, of what is prescribed

for the actual celebration of Mass, whether in word or in action, can be

excused from the guilt of, at least, venial sin. It is commonly held this does

not apply to what we have said of the preparation for the sacrifice and

thanksgiving after it. Words half pronounced, genuflections half formed,

incomplete signs, and confused and hurried actions, may lead to grave

sacrilege. There are some who hurry over the Mass in such a way that the interrogation might be put regarding them

which Tertullian used for another purpose: “Sacrificat,

an insultat?” Of such ministers it might be said they are not Priests but

executioners, who insult the Passion of Jesus Christ; they are perfidious Jews,

who, instead of pleading for pardon, bring upon their souls everlasting malediction.

Add to this the scandal given by him who celebrates without devotion. The

people respected our Divine Saviour in the beginning of His public life, but

when they saw Him despised by the priests they lost all reverence for Him, and

cried out for His death. The greater number of authors, including Benedict

XIV., Clement IX., and other very learned Pontiffs, declare that the

celebration of the Sacrifice of the Mass should not occupy more than half an

hour, nor less than the third part of an hour. Such a space of time is

prudently considered sufficient, both to secure a due and reverent celebration and

to prevent weariness on the part of those assisting. Whoever fails herein

merits reprehension; but he who gets through the Mass in a less space of time

than a quarter of an hour is, as St. Alphonsus holds, guilty of mortal sin.

3. Fervour in Thanksgiving after Mass is a

sure proof that the Priest has offered the Sacrifice with a heart animated with

holy affections. If he has celebrated, with the fire of the love of God it will

not be easily extinguished in him. Every benefit claims its acknowledgment.

Now, let us consider what gratitude is due to God by the Priest who has been

just permitted to say Mass! “Oh! what an

abuse and what a shame,” cries out St. Alphonsus, “to behold so many Priests who, after having celebrated Holy Mass, after

having received from God the honour of offering to Him in sacrifice His own

Divine Son, and after having been fed with His most Sacred Body, with tongues

still purpled with His most Precious Blood, having hurried over some short

prayers coldly and inattentively, commence immediately to discourse of useless things

or of worldly business; or else go forth carrying about the streets Jesus

Christ, who is still reposing in their breasts under the sacramental species.”

With such might we deal, as the Venerable John of Avila once did with a Priest

who left the church immediately after having celebrated. He sent two clerics,

bearing lighted torches, to attend him, and they, when asked by the Priest what

they meant, replied: “We accompany the

Blessed Sacrament which you carry in your breast.” Alas! How sad: and yet

this is the fittest and most precious time to treat of our eternal salvation

and to gain new treasures of grace. This is the propitious hour in which we

should present to our Saviour devout offerings and thank Him for the privileges

just conferred. After Communion, as St. Teresa says, let us not lose so good an

opportunity of treating with God, since His Divine Majesty is not wont to

reward sparingly him from whom He receives a hearty welcome.

As long as the Sacramental

Species remain every act of virtue possesses greater value and merit, because

of the strict union which then exists between the soul and Jesus Christ, as He

Himself declared: “Qui manducat meam

carnem et bibit meum sanguinem, in me manet et ego in illo.” Therefore acts

performed at this time have the highest degree of efficacy and value, for, says

St. Chrysostom; “Ipsa re nos in suum

efficit corpus.” Jesus places Himself in the soul as on a throne, and He

seems to say to her, as He formerly did to the man born blind, “Quid tibi vis faciam?” . . . Would it

not then be most advisable that every Priest should entertain Himself with

Jesus Christ for half an hour after Mass, says St. Alphonsus; or even for a

quarter of an hour?

The first portion of the

time of thanksgiving should be devoted by the Priest to the recital, more with

his heart than with his lips, of the customary prayers proposed by the Church,

which are found in all Missals and Breviaries. The second part should be spent

in loving communion with Jesus, in sentiments of adoration, of thanksgiving, of

oblation, and of supplication. The Priest should pray for himself and for the

Church; he should pray for all the people in general, and in particular for

those of his own diocese, of his country ; for his relatives; for the living

and for the dead; for all the members of the Catholic Church; particularly for those under his own charge

(parishioners, penitents, etc.); he should pray for all, that all may come to

know, to love, and to serve God on earth, and so afterwards to glorify Him with

the angels and saints in Heaven.

Thursday, August 8, 2019

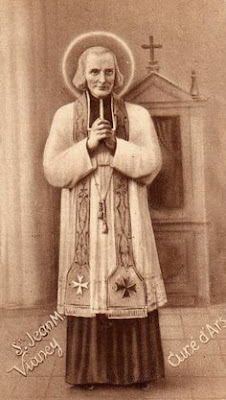

Saint John Mary Vianney

“The reputation of sanctity which surrounds the

name of M. Vianney makes all commendation superfluous. A common consent seems

to have numbered him, even while living, among the servants of God… It would seem

as if God were dealing with us now as He dealt with the world in the beginning

of the Gospel.

To the corrupt intellectual refinement of Greece

and Rome, He opposed the illiterate sanctity of the Apostles; to the spiritual

miseries of this age He opposes the simplicity of a man who in learning hardly

complied with the conditions required for Holy Orders, but, like the B. John

Colombini and St. Francis of Assisi, drew the souls of men to him by the

irresistible power of a supernatural life. It is a wholesome rebuke to the intellectual

pride of this age, inflated by science, that God has chosen from the midst of

the learned, as His instrument of surpassing works of grace upon the hearts of

men, one of the least cultivated of the pastors of His Church.” ~Abbé Monnin

“You cannot begin to speak of

St. John Mary Vianney without automatically calling to mind the picture of a

priest who was outstanding in a unique way in voluntary affliction of his body;

his only motives were the love of God and the desire for the salvation of the

souls of his neighbors, and this led him to abstain almost completely from food

and from sleep, to carry out the harshest kinds of penances, and to deny

himself with great strength of soul. Of course, not all of the faithful are

expected to adopt this kind of life; and yet divine providence has seen to it

that there has never been a time when the Church did not have some pastors of

souls of this kind who, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, did not

hesitate for a moment to enter on this path, most of all because this way of

life is particularly successful in bringing many men who have been drawn away

by the allurement of error and vice back to the path of good living.” ~John XXIII

“In a word, the one great truth taught us by the

whole history of the Curé of Ars is the all-sufficiency of supernatural

sanctity. A soul inhabited by the Holy Ghost becomes His instrument and His

organ in the salvation of men. To such a sanctity the smallness of natural gifts

is no hindrance, and the greatest intellectual power without it does little in

the order of grace; for souls are to be won to God, as God created and redeemed

them – by love and by compassion; and it was this which shone forth with a

surpassing splendor in all the life of this great servant of Jesus, and

concealed even the wonderful gifts of discernment and supernatural power with

which he was endowed.” ~Abbé Monnin

“The Spirit of God had been pleased to engrave on

the heart of this holy priest all that he was to know and to teach to others;

and it was the more deeply engraved, as that heart was the more pure, the more

detached, and empty of the vain science of men; like a clean and polished block

of marble, ready for the tool of the sculptor. The faith of the Curé of Ars was

his whole science; his book was Our Lord Jesus Christ. He sought for wisdom

nowhere but in Jesus Christ, in His death and in His cross. To him no other

wisdom was true, no other wisdom useful.” ~Abbé Monnin

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)